"); return false; } }); } }); }); function printExec(generatePage){ var s= s_gi(s_account), overrides = {}, name = 'print'; overrides.linkTrackVars = 'events,prop48,eVar48,eVar5'; overrides.linkTrackEvents = 'event3'; overrides.eVar5 = name; overrides.events = 'event3'; overrides.prop48 = s.eVar48 = s.pageName + ' | ' + name; s.tl(this, 'o', name, overrides, function() { if (generatePage) { window.open('/content/cro/en/health/chicken-safety.print.html','win2','status=no,toolbar=no,scrollbars=yes,titlebar=no,menubar=no,resizable=yes,width=640,height=480,directories=no,location=no'); } else { window.print(); } }); return false; } function emailExec(){ var s = s_gi(s_account), overrides = {}, name = 'email'; overrides.linkTrackVars = 'events,prop48,eVar48,eVar5'; overrides.linkTrackEvents = 'event3'; overrides.eVar5 = name; overrides.events = 'event3'; overrides.prop48 = s.eVar48 = s.pageName + ' | ' + name; s.tl(this, 'o', name, overrides); jQuery('.emailPopover').dialog('open'); return false; }

Most tested broilers were contaminated

Last updated: January 2010

You would think that after years of alarms about food safety—outbreaks of illness followed by renewed efforts at cleanup—a staple like chicken would be a lot safer to eat. But in our latest analysis of fresh, whole broilers bought at stores nationwide, two-thirds harbored salmonella and/or campylobacter, the leading bacterial causes of foodborne disease. That's a modest improvement since January 2007, when we found that eight of 10 broilers harbored those pathogens. But the numbers are still far too high, especially for campylobacter. Though the government has been talking about regulating it for years, it has yet to do so. (See Viewpoint.)

The message is clear: Consumers still can't let down their guard. They must cook chicken to at least 165° F and prevent raw chicken or its juices from touching any other food.

Illustration of chicken under microscope

Illustration by Keith Negley

Each year, salmonella and campylobacter from chicken and other food sources infect 3.4 million Americans, send 25,500 to hospitals, and kill about 500, according to estimates by the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But the problem might be even more widespread: Many people who get sick don't seek medical care, and many of those who do aren't screened for foodborne infections, says Donna Rosenbaum, executive director of Safe Tables Our Priority, a national nonprofit food-safety organization. What's more, the CDC reports that in about 20 percent of salmonella cases and 55 percent of campylobacter cases, the bugs have proved resistant to at least one antibiotic. For that reason, victims who are sick enough to need antibiotics might have to try two or more before finding one that helps.

Consumer Reports has been measuring contamination in store-bought chickens since 1998. For our latest analysis, we had an outside lab test 382 chickens bought last spring from more than 100 supermarkets, gourmet- and natural-food stores, and mass merchandisers in 22 states. We tested three top brands—Foster Farms, Perdue, and Tyson—as well as 30 nonorganic store brands, nine organic store brands, and nine organic name brands. Five of the organic brands were labeled "air-chilled" (a slaughterhouse process in which carcasses are refrigerated and may be misted, rather than dunked in cold chlorinated water).

Among our findings:

- Campylobacter was in 62 percent of the chickens, salmonella was in 14 percent, and both bacteria were in 9 percent. Only 34 percent of the birds were clear of both pathogens. That's double the percentage of clean birds we found in our 2007 report but far less than the 51 percent in our 2003 report.

- Among the cleanest overall were air-chilled broilers. About 40 percent harbored one or both pathogens. Eight Bell & Evans organic broilers, which are air chilled, were free of both, but our sample was too small to determine that all Bell & Evans broilers would be.

- Store-brand organic chickens had no salmonella at all, showing that it's possible for chicken to arrive in stores without that bacterium riding along. But as our tests showed, banishing one bug doesn't mean banishing both: 57 percent of those birds harbored campylobacter.

- The cleanest name-brand chickens were Perdue's: 56 percent were free of both pathogens. This is the first time since we began testing chicken that one major brand has fared significantly better than others across the board.

- Most contaminated were Tyson and Foster Farms chickens. More than 80 percent tested positive for one or both pathogens.

- Among all brands and types of broilers tested, 68 percent of the salmonella and 60 percent of the campylobacter organisms we analyzed showed resistance to one or more antibiotics.

Dirty birds

As they're raised, chickens can peck at droppings and insects that carry salmonella and campylobacter. The bacteria settle in their intestines, usually without harm, and the chickens contaminate their environment with infected feces. When the birds are slaughtered, intestinal bacteria can wind up on their carcasses.

To minimize contamination, processors of poultry (and of meat and seafood) follow federally mandated procedures collectively known as HACCP (pronounced hass-ip), which stands for Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point. Those measures are in effect in slaughterhouses and processing plants and are the consumer's main protection against contaminated chicken. HACCP, implemented for poultry and meat plants in 1997, requires companies to spell out where contamination might occur and then institute procedures to prevent, reduce, or eliminate it.

Inspectors for the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) monitor chicken companies' HACCP plans. They inspect carcasses and viscera for tumors, bruises, and other defects. During testing periods, they also pluck a broiler a day off the line and test it for the presence of salmonella. Plants that produce more than 12 salmonella-positive samples over 51 consecutive days of production fail to meet the FSIS-established performance standard, which triggers an FSIS review of the plant's HACCP plan. The plant would be expected to fix any problems; penalties are possible. To further motivate chicken processors to clean up their act, the USDA has begun publicly posting processors' salmonella test results online. (The data isn't archived, making it hard to assess a processor's performance over time.)

With this gentle prodding, poultry plants have improved, FSIS data indicate. Yet only 82 percent of broiler plants demonstrate what the FSIS calls "consistent process control." By the end of 2010, 90 percent of eligible plants should be able to meet that standard, according to FSIS projections.

That still leaves campylobacter. As we went to press in November, an FSIS spokesperson said that baseline data on the prevalence of campylobacter in broiler and turkey carcasses had been collected and were being analyzed and that draft performance standards based on those findings and a risk assessment would be ready by the year's end. FSIS testing for campylobacter would follow.

Carol L. Tucker-Foreman, distinguished fellow at the Consumer Federation of America's Food Policy Institute and a former USDA official, cited "at least a decade of promises and failures to develop campylobacter baseline data and a standard." But she acknowledged that the FSIS could deliver a report on baseline data by the end of 2009. "It is essential," she added, "to have a performance standard for campylobacter."

Behind the numbers

At 14 percent, the overall salmonella incidence is within the range we've seen in the past 12 years. In previous tests, the incidence ranged from 9 percent to 16 percent overall. Campylobacter incidence has varied more. Now it's 62 percent overall; in our previous tests it ranged from 42 percent to 81 percent.

When we took bacteria samples from contaminated chicken and analyzed their resistance to common antibiotics, most bugs could resist at least one antibiotic, and some evaded multiple classes of drugs. If a patient needs treatment, that might leave a doctor with poorer odds of choosing an effective antibiotic to fight infections that might be more stubborn.

The good news: All of the antibiotics were effective against 32 percent of the salmonella samples and 40 percent of the campylobacter samples. Back in January 2007, we reported that those figures were just 16 percent and 33 percent.

It's not surprising that we found antibiotic-resistant bacteria even in organic chickens, which are raised without antibiotics. "Chickens grown under organic conditions are given exposure to the outdoors, which provides contact with vermin such as rodents, insects, and birds that can carry and transmit these bacteria to chickens," said Michael Doyle, Ph.D., director of the University of Georgia's Center for Food Safety. Moreover, once genes for antibiotic resistance are in the gene pool of microbes, they can persist in the soil for years, even after the antibiotics are no longer in use.

The safeguards in place

Despite modest improvement in some numbers, our findings suggest that most companies' safeguards might be inadequate. To tease out what might account for Perdue's and Bell & Evans' relative success, we asked those companies as well as Tyson and Foster Farms whether they have added any food-safety measures in the past few years. We didn't reveal our test results.

Bruce Stewart-Brown, Perdue's vice president of food safety and quality, and a doctor of veterinary medicine, told us the company has increased its salmonella vaccinations over the past few years. That's designed to prevent chicks from picking up the bacterium from their mothers. Further protections, Stewart-Brown said, include an "all-in, all-out production model." Translation: Flocks are cleared out completely. Between flocks, farmers dry the empty chicken houses (which kills bacteria) and often use a product that temporarily changes the pH of the ground (to make it inhospitable to bacterial growth). Birds on each farm are the same age, so there are no older birds to contaminate newly arrived younger ones. "We also work closely with the farmers that raise our poultry," he said. "We make sure they isolate any other species of animals that might transfer microbiology to our chickens, use footwear and clothing control programs, and closely regulate visitation by outsiders."

Stewart-Brown also says that Perdue has implemented 25 food-safety steps at its processing plants.

Tom Stone, director of marketing at Bell & Evans, which produced those clean chickens, said the company has started packaging its products with a machine that seals the edges with film and shrinks the material, so there's no need for a "diaper" under the chicken to sop up fluids. "Our chickens are air-chilled and carry the ‘No Retained Water' statement," he said.

But listen to Foster Farms and Tyson and you'd think they would have been as clean. Robert O'Connor, vice president of technical services at Foster Farms and a doctor of veterinary medicine, cited the company's use of "the most technologically advanced and proven systems available." Tyson spokesman Gary Mickelson said his company's safeguards include keeping hatcheries sanitized, vaccinating some breeder stock against salmonella, and ensuring proper refrigeration during product delivery.

Our own experts say that controlling the spread of bacteria is a matter of being vigilant and taking many small steps, from hatchery to store, rather than relying on one magic bullet. A May 2008 release of USDA compliance guidelines for the poultry industry recommends 37 "best practices," including controlling litter moisture in chicken houses and continuously rinsing carcasses and equipment in processing plants. Chicken producers that follow good practices in the hatchery and on the farm and abide by those government guidelines should be able to produce fewer chickens that harbor salmonella, though not necessarily campylobacter.

What you can do

Too often, America's food-safety net has holes. Although Perdue chickens were cleaner than other big brands in our tests, and most air-chilled organic brands were especially clean, our tests are a snapshot in time and no type has been consistently low enough in pathogens to recommend over all others. Buying cleaner chicken may improve your odds if you fail to prepare chicken carefully. If you choose organic, be aware that it cost us up to $4.55 more per pound than the rest.

Whatever bird you buy, one slipup and you're at risk. Most important is to cook chicken to at least 165° F. Even if it's no longer pink, it can still harbor bacteria, so use a meat thermometer. The Polder THM-360, $30, and Taylor Weekend Warrior 806, $16, were excellent in our tests. Other tips:

- Make chicken one of the last items you buy before heading to the checkout line.

- Choose chicken that is well wrapped and at the bottom of the case, where the temperature should be coolest.

- Place chicken in a plastic bag like those in the produce department to keep juices from leaking.

- If you'll cook the chicken within a couple of days, store it at 40° F or below. Otherwise, freeze it.

- Thaw frozen chicken in a refrigerator, inside its packaging and on a plate, or on a plate in a microwave oven. Never thaw it on a counter: When the inside is still frozen, the outside can warm up, providing a breeding ground for bacteria. Cook chicken thawed in a microwave oven right away.

- Don't return cooked meat to the plate that held it raw.

- Refrigerate or freeze leftovers within 2 hours of cooking.

For more ways to help ensure that your food is safe, go to our Web site at www.BuySafeEatWell.org.

Sickened by chicken?

Michele Lundell, 53, of Apple Valley, Minn., became ill from campylobacter.

Within a few days of eating salad at a Minnesota restaurant in February 2009, Michele Lundell, a supervisor for a company that makes plastic tubing, experienced diarrhea, fever, and headache. "I kept getting sicker and sicker," she recalled. A test confirmed campylobacter. After her doctor prescribed antibiotics, Lundell said, she felt better for about a day, but then "all the same symptoms came back." She said she was hospitalized for six days. A Minnesota Department of Health investigation found that 10 people who had eaten at the restaurant were stricken with campylobacter and that the lettuce was most likely contaminated by raw or undercooked chicken. Lundell said she hasn't fully recovered. "It's hard to believe," she said, "that a person goes out to eat and gets so sick that it changes your life."

Science lesson: A little bit can make you sick

As few as 15 salmonella or 400 campylobacter organisms can make you ill. The salmonella found in raw poultry, meats, seafood, and produce can cause nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, fever, and headache, sometimes followed by arthritis symptoms. Campylobacter is found mainly in raw chicken. It wasn't recognized as a human pathogen until 1977, but it is now one of the most common causes of bacterial foodborne illness. The usual symptoms are diarrhea, often with fever, abdominal pain, nausea, headache, and muscle pain. Rarer are complications such as arthritis, meningitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, a potentially fatal neurological condition.

From henhouse to your house

The government's food-safety rules require chicken processors to identify "critical control points" where contamination might occur, then establish procedures for preventing, eliminating, or reducing those hazards. As our tests show, nothing guarantees a clean chicken. The contamination rate can vary with what the birds are fed, the preventive measures used, growing conditions, and the time of year, says Michael Doyle, Ph.D., director of the University of Georgia's Center for Food Safety. The procedures differ among plants; those outlined here are a possible scenario.

In the hatchery

Some chicks are contaminated with salmonella from their mothers or their own shells during hatching. Others ingest bacteria from their surroundings. Live birds infected with campylobacter or salmonella usually show no symptoms. To reduce the risk to people, some companies vaccinate hens and chicks against salmonella.

In the chicken house

Usually a new flock of thousands of chicks is trucked to a house run by a farmer according to the poultry producer's specifications. Chickens habitually peck the ground, ingesting bacteria from litter and feces, and could be exposed to vermin. Companies try to keep germ carriers away and continuously monitor the flocks' general health. Antibiotics are used to prevent or treat illness and might also be given to speed chickens' growth. But treated birds can't be sold as USDA-certified organic.

On the road

Chickens travel to the processing plant in cages. Filth can spread.

Processing plant

See In the processing plant.

After processing

Companies take steps to ensure their packaged chickens are properly refrigerated during shipping and delivery to market. Federal regulations require transport at a temperature no higher than 40° F.

In the store

Improper temperature or handling can introduce bacteria or cause them to multiply.

In your kitchen

Cooking chicken thoroughly, to at least 165° F, and washing anything that comes in contact with raw chicken greatly reduces risk.

In the processing plant

Birds are stunned, killed, and bled.

Scalding. Hot water loosens feathers for easier plucking. Some bacteria on feathers, feet, and skin are killed, but others float from one bird to another. Carcasses are washed. Critical control point Check temperature and pH of water.

Defeathering. A machine's rubber fingers pluck feathers and remove the outermost layer of skin. Contaminated fingers can spread bacteria from carcass to carcass.

USDA visual inspection. After internal organs are removed, a Department of Agriculture inspector checks carcasses and viscera for signs of disease, bruises, and other defects.

Washing. Birds are sprayed with chlorinated water or other washes to reduce bacteria and are checked for visible fecal matter. Chickens that pass muster are chilled; those that fail are reprocessed or discarded. Critical control point Record chlorine level and adjust if necessary.

Chilling. To prevent spoilage, carcasses are submerged in icy chlorinated water or air-chilled to lower their internal temperature to 40° F or less. When chickens emerge, USDA inspectors grade them for quality. At this stage, the USDA conducts salmonella testing, and the plant conducts one test for E. coli per 22,000 birds. Critical control point Monitor chlorine level of chiller or temperature of air-chill room; check internal temperature of birds.

Cut-up and packaging area. Birds are cut into pieces if necessary, packaged, and shipped. Critical control point Check for metal fragments in packaged poultry.

Talk the talk

Certified Humane Raised and Handled. For starters, the chicken had access to clean food and water, according to third-party inspectors with expertise in animal welfare.

Free-range, free-roaming. The chicken has had access to the outdoors, even if that means only that the door to the chicken house was left open briefly each day.

Fresh. The carcass's internal temperature hasn't dropped below 24° F. Still, the chicken might be partly frozen.

Kosher. The chicken was prepared according to Jewish dietary laws. Salt was added as part of the process.

Natural. The chicken was "minimally processed" in a way that didn't fundamentally alter the raw product. It has no artificial ingredients, preservatives, or added color.

No antibiotics administered. Don't assume this was verified unless you also see the label "USDA organic."

No hormones. Pointless; the USDA prohibits the use of hormones in raising poultry.

USDA organic. A USDA-accredited certifier has checked that the chicken company followed standards: Chickens were raised without antibiotics, ate 100 percent organic feed with no animal byproducts, and could go outdoors (though they might not have). For more about labels, go to our affiliate Web site at www.GreenerChoices.org.

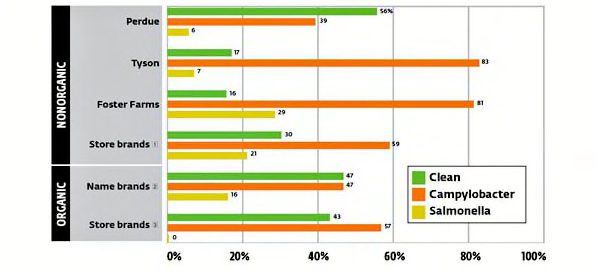

Levels of contamination

Below, the percentages of broilers that tested positive for campylobacter, salmonella, or neither (clean). We analyzed 70 chickens from each major brand, 66 from nonorganic store brands, 62 from organic name brands, and 44 from organic store brands. Figures are averages for store brands (both organic and nonorganic) and for organic name brands. Totals may exceed 100 percent because some broilers harbored both pathogens.

1. AJ's, Acme, Albertsons, America's Choice, Diebergs, Earth Fare, Fiesta, Fresh & Easy, Giant, Giant Eagle, Harris Teeter, Harry's, Hill Country Fare, Jewel, King Sooper, Kroger Value, Market Pantry, Nature's Promise, Publix, Roundy's, Safeway, Schnucks, Shaws, Shop 'n Save, Sweetbay, Tops, Wegmans, White Gem, Wild Harvest, Whole Foods.

2. Bell & Evans, Coastal Range, Coleman, D'Artagnan, Eberly's, MBA Brand Smart Chicken, Mary's, Pollo Rosso, Rosie.

3. Central Market HEB, O Organics (Safeway), Pacific Village (New Seasons), Private Selection Organic Fred Meyer, Private Selection Organic King Sooper, Private Selection Organic Kroger, Trader Joe's, Wegmans, Whole Foods.

Resistance to antibiotics

Some antibiotics important for humans are fed to nonorganic chickens to speed growth or prevent or treat illness. But bacteria may evolve to become immune to antibiotics, at which point the drugs become less effective in treating people. We took 53 salmonella samples and 103 campylobacter samples from chickens and determined what percentage of samples resisted antibiotics that usually work against those pathogens. "Resistant" indicates the percentage of bacteria that could survive a normal dose of the drug. Each color represents a class of antibiotics. Within classes, drugs are in alphabetical order.

| Salmonella drug | Resistant (a) |

|---|---|

| Gentamicin | 4% |

| Kanamycin | 17 |

| Streptomycin | 34 |

| Cefoxitin | 28 |

| Ceftiofur | 30 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0 (b) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 28 |

| Ampicillin | 30 |

| Chloramphenicol | 2 |

| Nalidixic acid | 2 |

| Sulfisoxazole | 21 |

| Tetracycline | 49 |

| One or more drugs | 68 |

| Campylobacter drug | Resistant (c) |

|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | 18% |

| Nalidixic acid | 21 |

| Tetracycline | 49 |

| One or more drugs | 60 |

(a) Tested drugs that were effective against salmonella: Amikacin, Ciprofloxacin, and Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole. (b) 17% of samples were somewhat resistant: Ceftriaxone inhibited bacterial growth but didn't stop it. (c) Tested drugs that were effective against campylobacter: Gentamicin, Azithromycin, Erythromycin, Telithromycin, Clindamycin, and Florfenicol.